Table Of Contents:

What is vector search?

Applications of vector search

What is a vector database?

TileDB as a Vector Database

Vector search in TileDB

Differentiation of TileDB

Roadmap and the ultimate vision

What’s Next?

Vector databases have recently gained popularity due to the advent of Generative AI and the proliferation of large language models (LLMs). In this blog we are officially announcing TileDB’s vector search support, which is what vector databases revolve around.

TileDB is an array database, and its main strength is that it can morph into practically any data modality and application, delivering unprecedented performance and alleviating the data infrastructure in an organization. A vector is simply a 1D array, therefore, TileDB is the most natural database choice for delivering amazing vector search functionality.

We spent many years building a powerful array-based engine, which allowed us to pretty quickly enhance our database with vector search capabilities in a new library called TileDB-Vector-Search. Here is why you should care:

TileDB is more than 8x faster than FAISS (specifically for algorithm

IVF_FLATbased on k-means), one of the most popular vector search librariesTileDB works on any storage backend, including scalable and inexpensive cloud object stores

TileDB has a completely serverless, massively distributed compute infrastructure and can handle billions of vectors and tens of thousands of queries per second

TileDB is a single, unified solution that manages the vector embeddings along with the raw original data (e.g., images, text files, etc), the ML embedding models, and all the other data modalities in your application (tables, genomics, point clouds, etc).

You can get a lot of value from TileDB as a vector database either from our open-source offering (MIT License), or our enterprise-grade commercial product.

In the remainder of this article I will elaborate on all the above. Specifically, I will cover:

The basics on vector search and vector databases to provide context even for those not familiar with the space

The necessary background on arrays and TileDB

How TileDB actually implements vector search functionality and why it is the natural choice as your vector database

Initial quantitative and qualitative comparisons versus other vector search solutions

Despite its powerful vector search capabilities, TileDB is so much more than a vector database. I will conclude this article by outlining our roadmap and TileDB’s ultimate vision to completely redefine data management as we know it. Enjoy!

What is vector search?

Vector search (aka similarity search or semantic search or nearest neighbor search) is not new, it’s been around for literally decades in various forms. I spent several years during my PhD studying one of its applications, mainly time series similarity search. Vector search became extremely hot after ChatGPT made LLMs incredibly popular. Note though that vector search is useful even outside of the LLM realm. In this section I define the general problem of vector search, and in the next I outline some exciting applications.

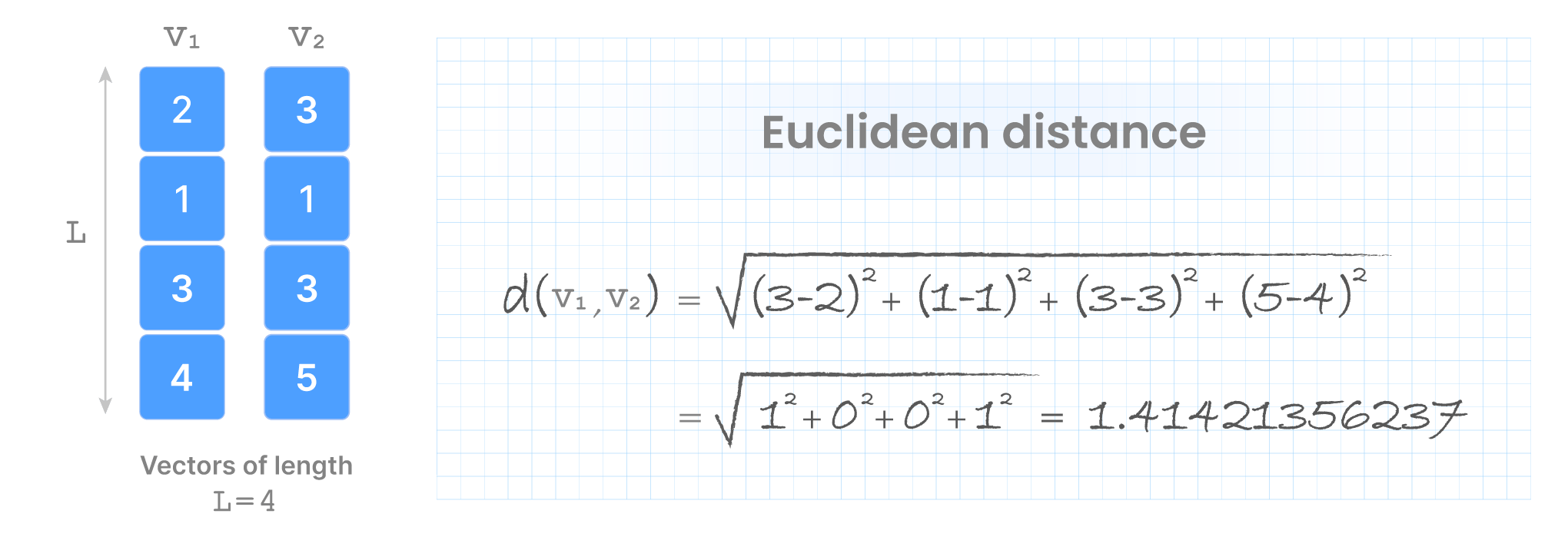

You can think of a vector as an (ordered) list of numbers. The number of elements in that vector is often called dimensionality, although I will argue later that this is a bit confusing when you move to the multi-dimensional array space. For now, I will just call it the vector length. Given two vectors v1 and v2 of equal length L, their distance is a function d(v1, v2). The smaller the distance value, the more similar the vectors. The distance is application-specific, but typical options include Euclidean, dot product, cosine, and others.

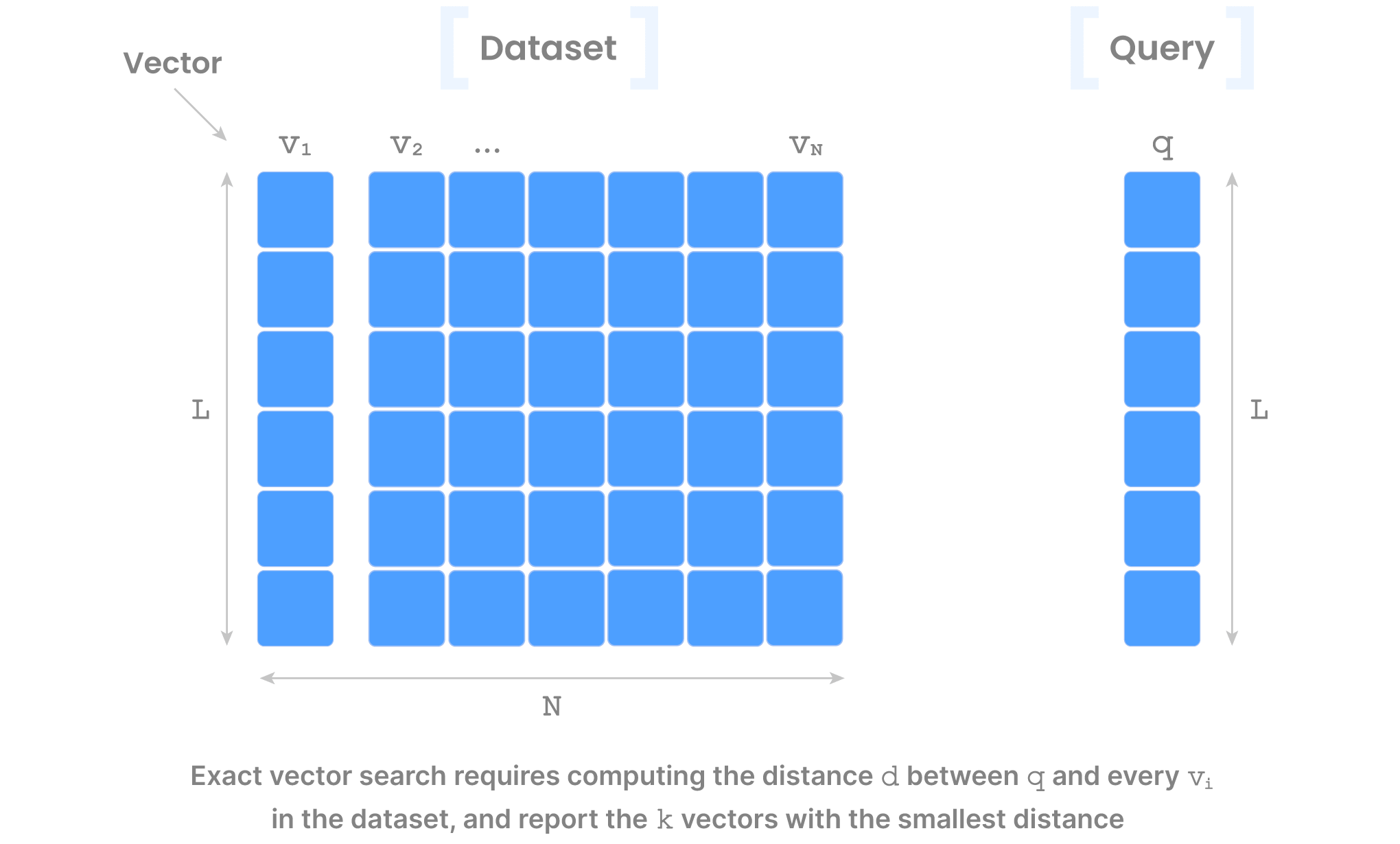

The problem of vector search involves a dataset of N vectors of length L, a query vector q (also of length L), and a distance function d, and returns the k most similar vectors from the dataset to the query q (i.e., those with the smallest distance to q).

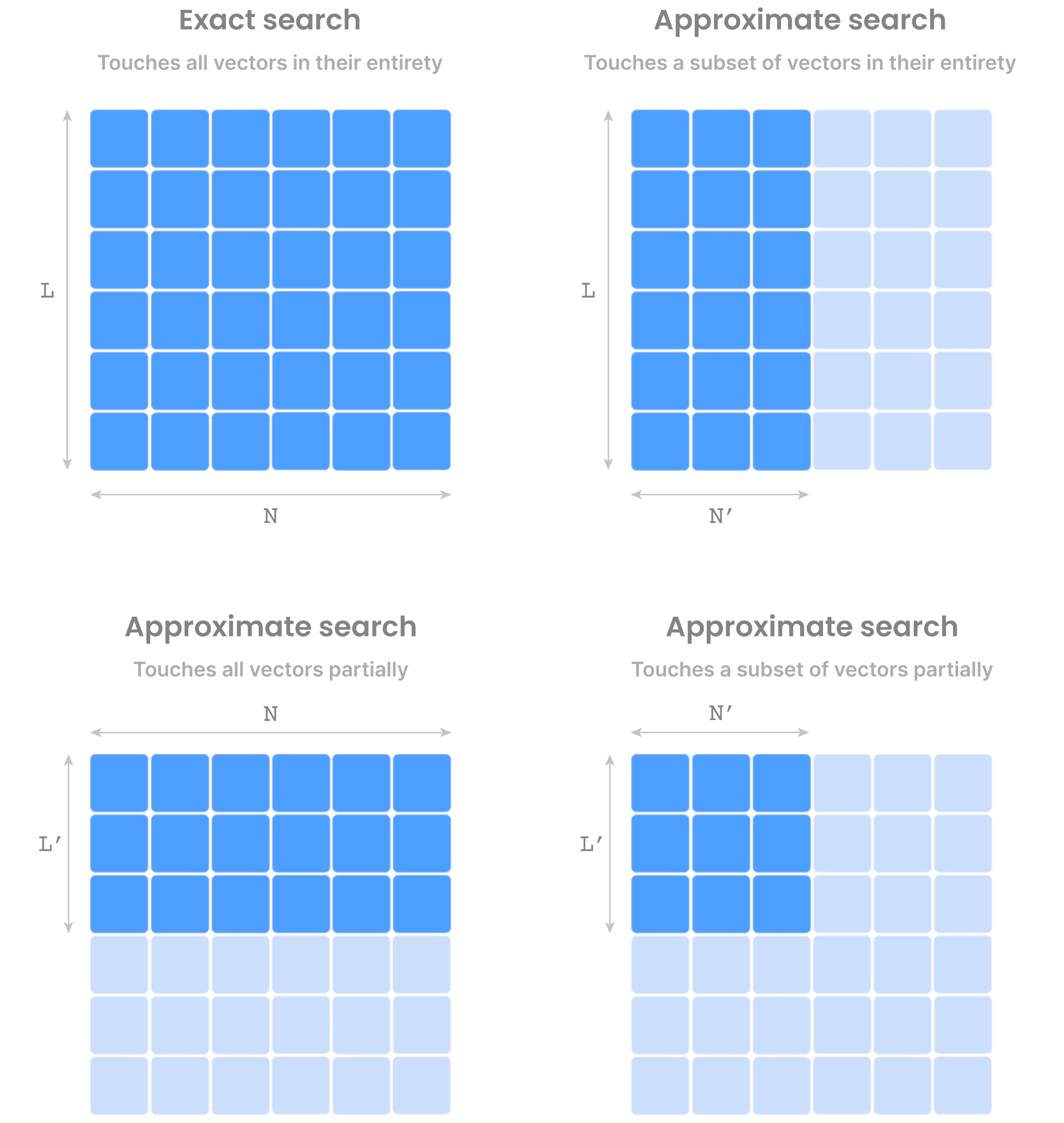

The reason why this problem is extremely interesting is because the number Nof vectors in the dataset may be in the order of billions, and length L in the order of thousands. Storing the vector dataset, as well as computing the distance of qto all these N vectors in a brute-force manner can be extremely expensive. This brute-force algorithm is typically called FLAT in the vector database world, and despite being so expensive, it is an exact algorithm in that it will always return the accurate result. In more technical terms, FLAT has 100% recall, defined as True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives).

This is where approximate vector search (aka approximate similarity search or approximate nearest neighbors or simply ANN) comes into play. The goal is to somehow reduce the search space, using a variety of creative techniques. Without getting into too much detail here, those techniques seek to either reduce the number of vectors N, or the length L (this is also often called dimensionality reduction in the literature) or both. And there are maaaaaany research papers on this problem. What is important to emphasize here is that all those techniques trade accuracy (i.e., recall) for performance (since now the search space is significantly smaller than N x L).

That’s all you really need to know at the moment about vector search. Now, on to why this is an exciting problem in the real world.

Applications of vector search

One of the applications of vector search that had caught my attention a very long time ago was in time series. Each vector represents a time series (such as stock tick data). For a given query (e.g., a time series window of a particular stock), the problem was to find similar patterns in a large database of other time series (e.g., to discover correlations).

Another application is searching for similar images or text documents. Comparing two images pixel by pixel doesn’t give you too much insight as to whether those are similar. For example, both images may contain cats, but in one image the cat may be at the top right corner and in the other at the bottom left. Although these two images are not identical, they are more similar to another image that contains a tree. Similarly, you may have two PDF documents that talk about Aristotle but using completely different sentences. Although not identical, those PDFs are more similar to each other than what they are to a PDF that talks about genomics.

One way to solve this problem is to manually add millions of labels to all images and documents and define some kind of text search to determine similarity. That would be extremely cumbersome and still we might miss something interesting if we labeled an image with “rose” and searched for “flower”. Can we do better than that?

Enter the vector embedding models. These are algorithms and machine learning models that have been trained on large quantities of data. For each data type (e.g., image versus text) there may be different embedding models with different effectiveness. The job of these models is to take as input data (e.g., an image or a PDF) and output – you guessed it – a vector. Think of this vector as magically compressed information about the data (e.g., the fact that an image contains a cat, the blue color is more pronounced, etc). The truly magical thing about these vectors is that they can be compared using a distance function to determine their similarity, exactly as I explained in the previous section. Therefore, searching in a huge database of data items (images, documents, audio, video and pretty much any other data type) for those that look like your query reduces to (i) producing vectors for all data in the dataset and the query using an embedding model and (ii) performing vector search.

As I mentioned before, the above applications have been around for a very long time. What made vector search extremely cool is its use in LLMs. An LLM (e.g., ChatGPT, Llama, and others) is a machine learning model that can be thought of as yet another black box which takes as input data, typically in the form of a request in natural language, and produces (surprisingly spectacular) answers. Of course, these answers depend on the information the LLM has been trained on.

Here is where things become very interesting. The LLM has no idea about your own private data, yet you want to use the LLM to answer questions about your data. For example, your data could be your product documentation, personal notes, research paper PDFs, a collection of songs, and more. Training the LLM from scratch to encompass your data is expensive (correction: extremely expensive). The second option is to fine-tune an existing LLM, which is not as bad in terms of cost, but it’s still expensive and you will need to constantly fine-tune your LLM as your data gets updated. This brings us to the third option: context-aware LLMs.

The idea behind context-aware LLMs is simple. Instead of just asking an existing LLM a question, you can provide additional information (i.e., context) and tell the LLM to answer the question taking into account the context. For example, suppose you’d like to “write a summary about dimensionality reduction”, but focusing only on the research articles you have downloaded on your machine. What you can do is alter the prompt to “write a summary about dimensionality reduction using my downloaded research articles”. There is indeed a way to do this with something called agents and tools, but do not fret right now over those, we’ll cover them in a subsequent blog.

The problem with the above is that you may have stored thousands of articles in your database and most LLMs have limitations on how much context you can provide. Enter vector search! You can use an embedding model to create vector embeddings for every article in your database, and instruct the tools and agents hooked with your LLM to create a vector about “dimensionality reduction” and return the top, say, 3 articles from your database that are similar to this vector. Finally, the LLM prompt will contain only those top 3 PDFs as context.

Summarizing, vector search has application outside of LLMs, but its most popular use case today is arguably in context-aware LLMs. But how do vector databases fit in this picture?

What is a vector database?

A vector database, like any other database managing other data types, is responsible for:

Storing the vector data in some format, on some storage medium

Managing updates, potentially offering versioning and time traveling

Enforcing authentication, access control and logging

Performing efficient vector search using various algorithms, distances and indexes

Vector databases differ in the way they implement any subset of the above four bullet points, as well as of course performance (typically measured in terms of latency and queries per second, or QPS). Here is where things start getting confusing. Today you hear a lot about special-purpose vector databases, which have been designed specifically to handle vectors and perform vector search. This category includes Pinecone, Milvus, Weaviate, qdrant and Chroma. However, there are also libraries (not databases per se) that offer similar functionality, such as FAISS. There are open-source options, closed-source options, or a mix. And here is where it gets worse: pretty much every single database system out there (be it tabular, key-value, time series – you name it) started offering “vector search capabilities” as part of their database product, due to the recent hype around vector databases. This is because they can store vectors as blobs, build a couple of indexes on top, as well as operators to perform vector search. Compared to the colossal software they have already developed in their product (building databases is very very hard), the vector search capabilities are a fairly easy development task (since there is also no IP around the vector search algorithms).

So how do you choose a vector database from the myriads of emerging options? For example, you can probably go a very long way just by using the open-source FAISS library, but you won’t have enterprise-grade security features. On the other hand, you can use Pinecone or Milvus, but in order to scale to billions of vectors you’ll probably need numerous machines up and running constantly, seeing your operational cost skyrocketing. In other words, what you need to understand is the deployment setting behind each solution, which determines both performance and cost.

Here are the main deployment settings:

Single-server, in-memory: All the vectors and indexes reside in the RAM of a single machine. This means that you need to have a big enough memory to hold all the vector data. This probably yields the best performance, but targets relatively small datasets. An example of this is FAISS.

Single-server, out-of-core: All vectors reside on the local storage of a single machine, whereas the indexes (or portion of them) can reside in RAM. The query is performed by progressively bringing more data from disk to RAM for processing. This targets larger datasets, but you are still constrained by the capacity of a single machine and your performance is impacted by the disk-to-memory IO. An example of this is DiskANN.

Multi-server, in-memory: To address the RAM limits of a single machine, in this category you have a database that runs distributed over multiple machines, whose memory collectively stores the entire vector dataset and indexes. Performance is pretty high since all data is always processed directly in main memory. However, this can get extremely expensive for larger datasets, as you may need to scale to numerous machines. An example of this is Pinecone.

Serverless, cloud store: All the data is stored on a cloud object store (e.g., AWS S3). The database has infrastructure to process any query in a way that seems “serverless” to the user (i.e., the user does not need to set up or even specify any machines to run the query). Performance depends on how well the underlying storage engine is implemented for cloud object stores and in general the whole serverless infrastructure, but there are lower bounds on latency because now an entire cloud infrastructure lies in between the user and the data. An example of this is Activeloop.

You now have all the background you need before digging into TileDB and understanding what it brings to the table and how it compares to everyone else.

TileDB as a Vector Database

What is TileDB?

TileDB was a research project I started when I was at Intel Labs and MIT between 2014 and 2017. It stemmed from my observations that (1) there are numerous tabular databases, which fail to address more complex data that is not naturally represented as tables, (2) there are numerous special-purpose databases, which are very niche, serving only a very specific data type and failing to address all others. My research hypothesis was this: “can we build a single database system that can accommodate all data types and use cases”? Granted, this sounds audacious and such a system would take an enormous time to build, but can it exist? And if it can, how would it universally store all types of data? That led me to using multi-dimensional arrays as the foundation for TileDB, which have proven over the years to be the right choice. This is because, instead of trying to unnaturally fit the data into tables, or key-values, or documents, or another stiff data structure, multi-dimensional arrays do the exact opposite: they morph into the data, perfectly capturing their properties and query workloads. Thus, they can deliver generality with superb performance.

At a very high level, TileDB is an array database. Arrays are a very flexible data structure that can have any number of dimensions, store any type of data within each of its elements (called cells), and can be dense (when all cells must have a value) or sparse (when the majority of the cells are empty). The sky's the limit when it comes to what kind of data and applications arrays can capture. You can read all about arrays and their applications in my blog Why Arrays as a Universal Data Model. And if you think that an array database is yet another niche, specialized database, that blog also demonstrates how arrays subsume tables. In other words, arrays are not specialized, but instead they are general, treating tables as a special case of arrays.

Now, here is something that you may have already guessed: a vector is simply a 1D dense array. And although vector databases call those vectors as high-dimensional, from an array perspective they are just one-dimensional with a fairly small domain (typically up to a few thousand elements). This is the reason why I will avoid calling the vector length as “dimensionality” (and just call it “length” instead), as I’d like to reserve “dimensionality” for the number of dimensions in an array.

As a side note, a lot of people are using (or, rather, abusing) the term “tensor” to pretty much mean “multi-dimensional array”. I’d like to suggest staying clear from that term, unless you are speaking with physicists or mathematicians. There are mathematical nuances in tensors that go beyond the scope of this article. The array model I present in the aforementioned blog (although mathematically rather simplistic) is more than sufficient in the data structures and databases context.

We built TileDB from the ground up, starting from the data model, data format and storage engine. All these are implemented in the TileDB Embedded open-source package (MIT License). This is a C++ library that comes with a C and C++ API and offers the following:

Support for both dense and sparse arrays

Support for tables and key-value stores (via sparse arrays)

Cloud storage (AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage)

Chunked (tiled) arrays

Multiple compression, encryption and checksum filters

Fully multi-threaded implementation with parallel IO

Data versioning (rapid updates, time traveling, ACID without synchronization)

Array metadata and groups

On top of this library, we developed numerous APIs (Python, R, Java, Go, C#, Javascript and more), integrations (Spark, Dask, MariaDB, Presto, Trino and more) and application-specific packages (TileDB-VCF, TileDB-SOMA, and more).

The TileDB open-source ecosystem and the morphing capabilities of the underlying arrays allow you to build any special-purpose, super efficient, data management system. However, the core TileDB Embedded library lacks security features, automation for scalable computing, and other functionality that data scientists and data engineers would like to see in a data management system.

To provide such extended capabilities, we built TileDB Cloud, a full-fledged data management platform that offers:

A serverless computational framework based on user-defined functions (UDFs) and task graphs, used from a variety of languages. Using this framework you can implement practically anything, from a simple lambda function, to large ETL workflows, genomics or ML pipelines, and sophisticated distributed algorithms.

Advanced secure management capabilities, such authentication, access control for easy sharing, and logging for auditing purposes.

A holistic catalog over all your data and code assets for easy discoverability.

Computational environments such as Jupyter notebooks and dashboards.

The open-source TileDB Embedded array data engine and ancillary packages, along with the powerful enterprise capabilities of TileDB Cloud, enable data engineers to build their own special-purpose products. But they also allow the TileDB team to develop tailored solutions for important applications (such as in Life Sciences, Geospatial, ML, Analytics, and more), all using the array data model and core computational and management features. And one of those tailored solutions we developed is vector search!

Vector search in TileDB

Let’s return to vector search, starting from the fact that we have a set of Nvectors each of length L that we need to manage in TileDB. All we need to do is store this dataset in a NxL matrix, i.e., a 2D array. TileDB natively stores arrays and, thus, ingestion, all updates with versioning and time traveling, and reading (aka slicing) are already handled by TileDB Embedded — we literally didn’t need to build any extra code for that.

The additional things we had to build were:

Indexes for fast (approximate) similarity search

The fast (approximate) similarity search itself

APIs that are more familiar to folks using vector databases

We developed all the above in an open-source package called TileDB-Vector-Search, which is built on top of TileDB Embedded. Currently, this package supports:

A C++ and Python API

FLAT(brute-force) andIVF_FLATalgorithms (all others are under development)Euclidean distance (other metrics are under development)

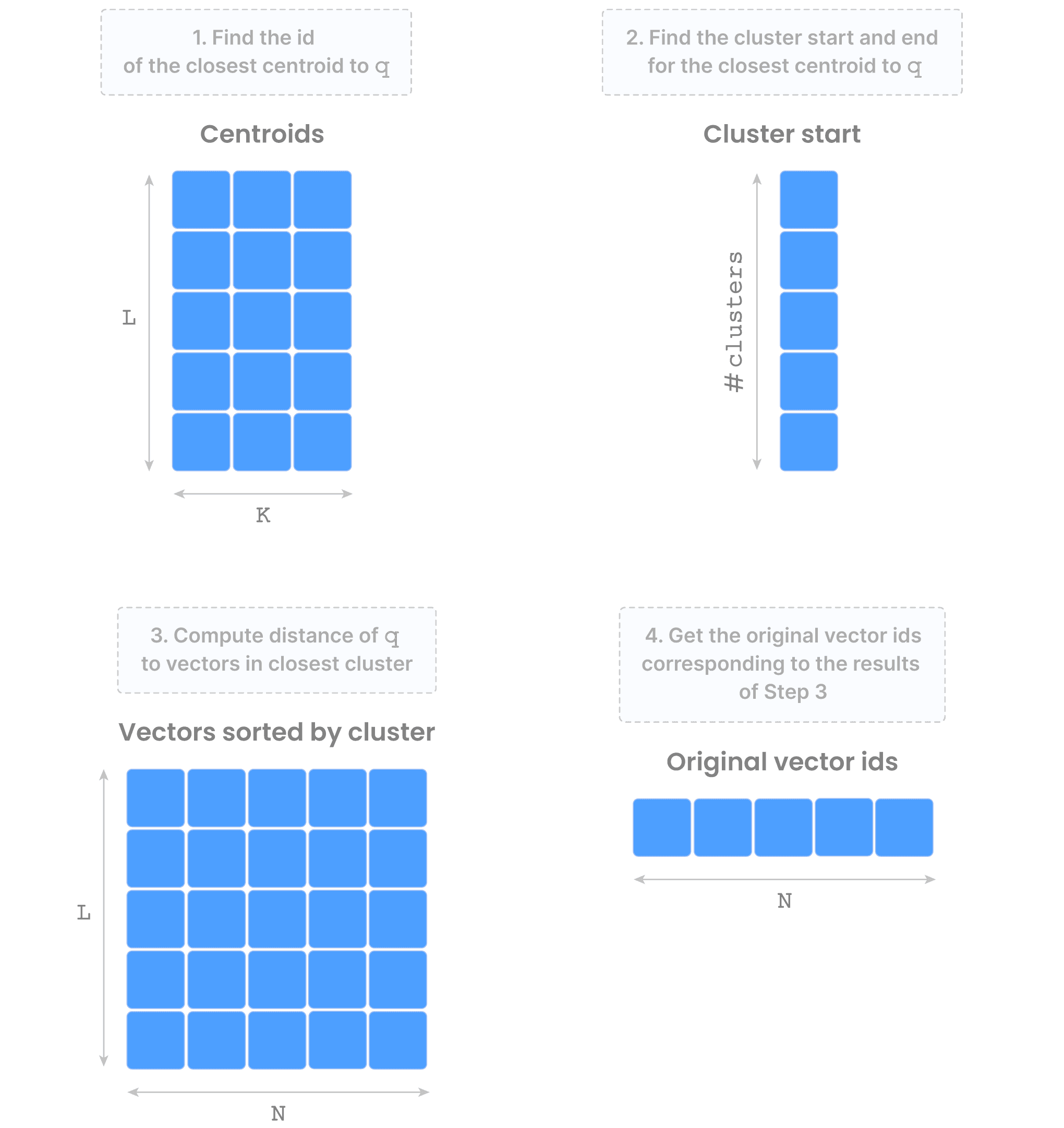

FLAT is straightforward and rarely used for large datasets, but we included it for completeness. IVF_FLAT is based on K-means clustering. Effectively, TileDB computes K separate clusters (as well as their centroids) of the dataset vectors, shuffling them in a way such that vectors in the same cluster appear adjacent on storage (to minimize IO when retrieving those vectors). To answer a query, the search focuses only on a small number of clusters, based on the query’s proximity to their centroids. This is specified with a parameter called nprobe – the higher this value, the more expensive the search but the better the recall (i.e., the accuracy).

The figure below shows the arrays that comprise the “vector search asset”, which is represented in TileDB with a “group” (think of this as a virtual folder). The figure also shows the IVF_FLAT query process at a high level.

Now that you know how TileDB natively supports vector search, here are a few cool facts.

This implementation works in three out of the four of the deployment modes I outlined above:

Single-server, in-memory: Due to the way we store and process arrays in RAM, our

IVF_FLATperformance is spectacular; up to 8x faster than FAISS, serving over 60k queries per second based on SIFT 10M, and 2.7k queries per second on SIFT 1B.Single-server, out-of-core: TileDB has native, super efficient out-of-core support, so our vector search implementation in this mode inherited the high performance.

Serverless, cloud store: Due to the fact that we architected TileDB from the ground up to be serverless and work flawlessly on cloud object stores, our vector search implementation delivers superb performance even in this setting, providing unprecedented scalability to billions of vectors while minimizing operational costs.

TileDB supports batching of queries, i.e., it can dispatch hundreds of thousands of queries together in a bundle. We offer a very optimized implementation of batching, which amortizes some fixed, common costs across all queries, significantly increasing the queries per second (QPS).

The “serverless, cloud store” mode can leverage the TileDB Cloud distributed, serverless computing infrastructure to parallelize across both queries in a batch, as well as within a single query. This provides unprecedented scalability, QPS and real-time response times even in extreme querying scenarios.

Regarding the “multi-server, in-memory” mode, we are gathering some more feedback from users. Although it is easy to build (and you can probably build it yourselves leveraging just TileDB’s single-server, in-memory mode), we hypothesize that it is overkill for the users from an operational standpoint, especially in the presence of the more scalable and inexpensive options of “single-server, out-of-core” and “serverless, cloud store”. Please send us a note after you try out those other modes if they do not provide sufficient performance for your use case.

We have put together a nice quickstart guide to get you started on vector search with TileDB. You’ll be able to run a good portion of it locally on your laptops. In addition to the simple examples, we show you how to leverage distributed queries on TileDB Cloud, and we give you access to the public ANN_SIFT1B vector dataset, ingested in TileDB and accessible via TileDB Cloud. You just need to sign up to TileDB Cloud and we’ll give you free credits, so we got you fully covered for your evaluation.

I am assuming that you find all this awesome, but I bet you’d like to see how TileDB compares to the increasingly crowded vector database market, as well as where this leads, with TileDB being a universal database and all. Read on! :)

Differentiation of TileDB

There are many vector search solutions available, from special-purpose databases (i.e, databases built from scratch just for vector search) to libraries and extensions of existing databases. In summary, TileDB brings the following benefits to the table:

Performance: Vectors are arrays, and arrays are a native data structure in TileDB. As such, TileDB delivers spectacular performance, even under extreme scenarios.

Serverless: All deployment modes supported by TileDB are serverless, even when you need to outgrow your local machine and scale in the cloud. This has a direct impact on the operational cost, which TileDB minimizes.

Cloud-native: TileDB is uber optimized for object stores. As such, you can scale your vectors to cloud storage, while enjoying superb performance. Again, this leads to significant cost savings.

Multiple modalities: TileDB is not just a vector database. TileDB envisions to store, manage and analyze all your data, which includes the raw original data you generate your vectors from, as well as any other data your organization might require a powerful database for. Storing multiple data modalities in a single system (1) lowers your licensing costs, (2) simplifies your infrastructure and reduces data engineering, (3) eliminates the data silos enabling a more sane, holistic governance approach over all your data and code assets.

In addition to the above, here is a brief qualitative and quantitative comparison versus other solutions you might know:

FAISS is an open-source library developed by Facebook AI Research that provides diverse indexing and querying algorithms for vector search. Its focus is performing efficient similarity search using main-memory indices and leveraging the processing capabilities of single-server CPU and GPU resources. Though FAISS offers excellent performance and algorithmic support, it lacks database features such as security, access control, auditing and storing raw objects and metadata. In the “single-server, main memory” setting, TileDB outperforms the respective algorithm implementations of FAISS by up to 8x for 1 billion vectors.

Milvus is an open-source vector database developed by Zilliz. It focuses on providing scalable and efficient vector search functionalities in a database setting while also storing extra objects and metadata. With its new version Milvus 2.0, it targets a cloud-native distributed architecture. While offering DB features for vector search, Milvus only targets high QPS and low latency use cases using a distributed in-memory infrastructure that requires large maintenance and static infrastructure costs. Also its support for storing extra data and raw objects is not appropriately designed to handle the high dimensional objects often required for vector search (images, video, audio, etc). In the “single-server, main memory” setting TileDB outperforms the respective algorithm implementations of Milvus by up to 3x for 1 million vectors.

Pinecone is a cloud-based vector database service that is proprietary and optimized for real-time applications and machine learning workloads. It excels in delivering low-latency and high-throughput vector search capabilities. Similar to Milvus, it offers a distributed in-memory infrastructure hosted in the cloud, with added database features for vector search. However, Pinecone may not provide optimal performance for storing raw multi-dimensional objects, and it can incur significant static costs for infrastructure setup, even in scenarios where a high QPS setup is not necessary. Pinecone does not have an open-source offering and does not participate in the ann-benchmarks.

Chroma is an open source vector database built on NumPy (for distance metrics Euclidean, cosine, and inner-product) and hnswlib, with several database backends for storage. It is focused on text search for LLM use-cases, and provides integration with several Python libraries. At present, Chroma provides an in-process Python API; the Chroma company is developing a distributed implementation. Chroma does not yet participate in ann-benchmarks, and we have not benchmarked independently.

ActiveLoop is a company that specializes in storing multi-modal data like audio, video, image, and point cloud data, and making them accessible to machine learning processing pipelines. They have developed a product called DeepLake, which is a data lake specifically designed for deep learning. Activeloop also offers a vector search product that is designed to work in a serverless manner using cloud store and disk data. While they embrace “tensor” formats for storing raw objects, their data format is less generic than the multi-dimensional array format of TileDB. They also embrace a serverless compute, cloud native storage model for vector search but, based on our understanding, their implementation is quite primitive (without any sophisticated indexing and query algorithm implementation and without any knobs to tweak accuracy for cost and performance). In the “single-server, out-of-core” setting, TileDB outperforms the respective algorithm implementations of Activeloop by more than 10x.

pgvector is an open-source vector search extension for Postgres, supporting

IVF_FLATindexing with several distance metrics (Euclidean, cosine, inner product). All pgvector data transfer happens through SQL, which is likely to be a performance limitation in large-scale use. TileDB provides approximately 100x higher QPS at 95% recall vs pgvector on the ann-benchmarks.DiskANN is an open-source software library developed by Microsoft to support search problems that are too large to fit into the memory of a single machine. It is still a single-machine system, but it stores indices and partitioned full-precision vectors on a solid-state drive (SSD); PQ-compressed vectors are stored in memory. The primary approach for indexing is the graph-based Vamana algorithm, which improves over other graph-based algorithms such as HNSW and NSG. Adaptations of indexing and search strategies can be used with the DiskANN framework for different kinds of applications. As with other library approaches, database concerns are outside the scope of DiskANN.

Qdrant is an open source system implemented in Rust and backed by the startup Qdrant Solutions GmbH. It features a client-server architecture with REST and gRPC endpoints, and is available for both self-hosted usage and as a managed service. Qdrant only supports the HNSW index algorithm, but adds additional filtering with the capability to attach (indexed) payloads to the graph. Qdrant supports JSON “payload” data attached to vectors, but does not provide support for storage or slicing of array or multi-modal data. TileDB-Vector-Search provides approximately 5x QPS in batch mode vs Qdrant at 95% recall.

Weaviate is an open source system implemented in Go and backed by the startup Weaviate B.V. It features a client-server architecture with REST and GraphQL endpoints, available for self-hosted usage or as a managed service. Weaviate implements indexing with HNSW (optionally with product quantization to reduce memory usage). It includes integrations to generate vectors based on several popular models. Weaviate does not support storage or slicing of other data types. TileDB-Vector-Search provides approximately 10x QPS in batch mode vs Weaviate at 95% recall.

Roadmap and the ultimate vision

Our team is working hard on enhancing our current vector search offering. Specifically, you’ll soon see:

Updates: TileDB already has superb support for array / vector updates, versioning and time traveling. We are working on seamlessly updating the indexes when vectors are added, removed or altered (today you need to rebuild the indexes from scratch).

Other algorithms: We are currently implementing

IVF_PQandHNSW, but more will appear soon.Other distance metrics: We are adding other metrics such as dot product, cosine, Jaccard and more.

Additional query filters: In TileDB, you can associate any array with any other array and thus, you can effectively augment your vector dataset with additional, arbitrarily complex metadata. Coupled with TileDB’s SQL functionality, that will allow you to apply any extra query filters to augment and expedite your vector search. We are working on offering that as a streamlined experience using simple APIs within the TileDB-Vector-Search offering.

Integration with LLMs: We are working on integrations with tools such as LangChain, so that you can easily use TileDB as the vector store backing your favorite LLMs.

We are extremely excited about the vector search domain and the potential of Generative AI. But despite its powerful vector search capabilities, TileDB is more than a vector database. TileDB envisions to simplify your data infrastructure by unifying your diverse data into a single, modernized database system. And as LLMs are becoming more and more powerful leveraging multiple data modalities, TileDB is the natural choice for internally using LLMs to gain unprecedented insights on your diverse data, leveraging natural language as an API! Imagine extracting instant value from all your data, without thinking about code syntax in different programming languages, understanding the underlying peculiarities of the different data sources, or worrying about security and governance.

Stay tuned for more updates on how we are redefining the “database”!

What’s Next?

In this article, I described how TileDB implements vector search functionality and, thus, can act as a powerful vector database in your data infrastructure. In addition, I explained that TileDB is built on arrays, which can morph to capture a wide variety of use cases that go beyond vector search (such as analytics, genomics, geospatial and more). If you liked this article, I recommend you also watch our recent webinar Bridging Analytics, LLMs and data products in a single database, which I co-hosted with Sanjeev Mohan.

To learn more about TileDB-Vector-Search, check out the github repo and docs, or get kickstarted with the quickstart demo. We have a very long backlog on vector search, so look for more articles on our detailed benchmarks, internal engineering mechanics, and LLM integrations.

Feel free to contact us with your feedback and thoughts, follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter, join our Slack community, or read more about TileDB on our website and blog.

Meet the authors